Life A User's Manual By Georges Perec Pdf Sometimes there is a perfect time to read a book. Sometimes, there isn't. One could argue that, perfectionism is another part of being vulnerable.

| Author | Georges Perec |

|---|---|

| Original title | La Vie mode d'emploi |

| Translator | David Bellos |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Publisher | Hachette Littératures |

Publication date | 1978 |

| 1987 | |

| ISBN | 978-0-87923-751-6 (1978 paperback, first English translation) ISBN0-87923-751-1 (1987 hardcover) ISBN978-1-56792-373-5 (2008 paperback, revised translation) |

While knowing of Perec's constraints and plan in the structure of the novel can add considerably to a reader's experience, it is not necessary to even be aware of them to read Life: A User's Manual with enjoyment. The central plot of the book is the tale of Bartlebooth, an extremely wealthy English resident of 11 Rue Simon-Crubellier. Life A User's Manual By Georges Perec Pdf —Georges Perec, Life: A User's Manual. “T rue life, life finally discovered and illuminated, the only life there- fore really lived, is literature, that life which. To La Vie mode d'emploi (Life a User's Manual) by Georges 1 Georges Perec (1936-1982) was a French writer of Polish-Jewish origin. Life A User Manual Perec Pdf —Georges Perec, Life: A User's Manual. “T rue life, life finally discovered and illuminated, the only life there- fore really lived, is literature, that life which. To La Vie mode d'emploi (Life a. May 15, 1978 Life: A User's Manual is an unclassified masterpiece, a sprawling compendium as encyclopedic as Dante's Commedia and Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and, in its break with tradition, as inspiring as Joyce's Ulysses. Perec's spellbinding puzzle begins in an apartment block in the XVIIth arrondissement of. Life by Georges Perec, 256, download free ebooks, Download free PDF EPUB ebook. Georges Perec was a highly-regarded French novelist, filmmaker, and essayist. He was a member of the Oulipo group. Many of his novels and essays abound with experimental wordplay, lists, and attempts at classification, and they are usually tinged with melancholy.

Life: A User's Manual (the original title is La Vie mode d'emploi) is Georges Perec's most famous novel, published in 1978, first translated into English by David Bellos in 1987. Its title page describes it as 'novels', in the plural, the reasons for which become apparent on reading. Some critics have cited the work as an example of postmodern fiction, though Perec himself preferred to avoid labels and his only long term affiliation with any movement was with the Oulipo or OUvroir de LIttérature POtentielle.

La Vie mode d'emploi is a tapestry of interwoven stories and ideas as well as literary and historical allusions, based on the lives of the inhabitants of a fictitious Parisian apartment block, 11 rue Simon-Crubellier (no such street exists, although the quadrangle Perec claims Simon-Crubellier cuts through does exist in Paris XVII arrondissement). It was written according to a complex plan of writing constraints, and is primarily constructed from several elements, each adding a layer of complexity.

- 3Elements

Plot[edit]

Between World War I and II, a tremendously wealthy Englishman, Bartlebooth (whose name combines two literary characters, Herman Melville's Bartleby and Valery Larbaud's Barnabooth), devises a plan that will both occupy the remainder of his life and spend his entire fortune. First, he spends 10 years learning to paint watercolors under the tutelage of Valène, who also becomes a resident of 11 rue Simon-Crubellier. Then, he embarks on a 20-year trip around the world with his loyal servant Smautf (also a resident of 11 rue Simon-Crubellier), painting a watercolor of a different port roughly every two weeks for a total of 500 watercolors.

Bartlebooth then sends each painting back to France, where the paper is glued to a support board, and a carefully selected craftsman named Gaspard Winckler (also a resident of 11 rue Simon-Crubellier) cuts it into a jigsaw puzzle. Upon his return, Bartlebooth spends his time solving each jigsaw, re-creating the scene.

Each finished puzzle is treated to re-bind the paper with a special solution invented by Georges Morellet, another resident of 11 rue Simon-Crubellier. After the solution is applied, the wooden support is removed, and the painting is sent to the port where it was painted. Exactly 20 years to the day after it was painted, the painting is placed in a detergent solution until the colors dissolve, and the paper, blank except for the faint marks where it was cut and re-joined, is returned to Bartlebooth.

Ultimately, there would be nothing to show for 50 years of work: the project would leave absolutely no mark on the world. Unfortunately for Bartlebooth, Winckler's puzzles become increasingly difficult and Bartlebooth himself becomes blind. An art fanatic also intervenes in an attempt to stop Bartlebooth from destroying his art. Bartlebooth is forced to change his plans and have the watercolors burned in a furnace locally instead of couriered back to the sea, for fear of those involved in the task betraying him. By 1975, Bartlebooth is 16 months behind in his plans, and he dies while he is about to finish his 439th puzzle. The last hole in the puzzle is in the shape of the letter X while the piece that he is holding is in the shape of the letter W.

Structure[edit]

The entire block is primarily presented frozen in time, on June 23, 1975, just before 8 pm, moments after the death of Bartlebooth. Nonetheless, the constraints system creates hundreds of separate stories concerning the inhabitants of the block, past and present, and the other people in their lives. The story of Bartlebooth is the principal thread, but it interlinks with many others.

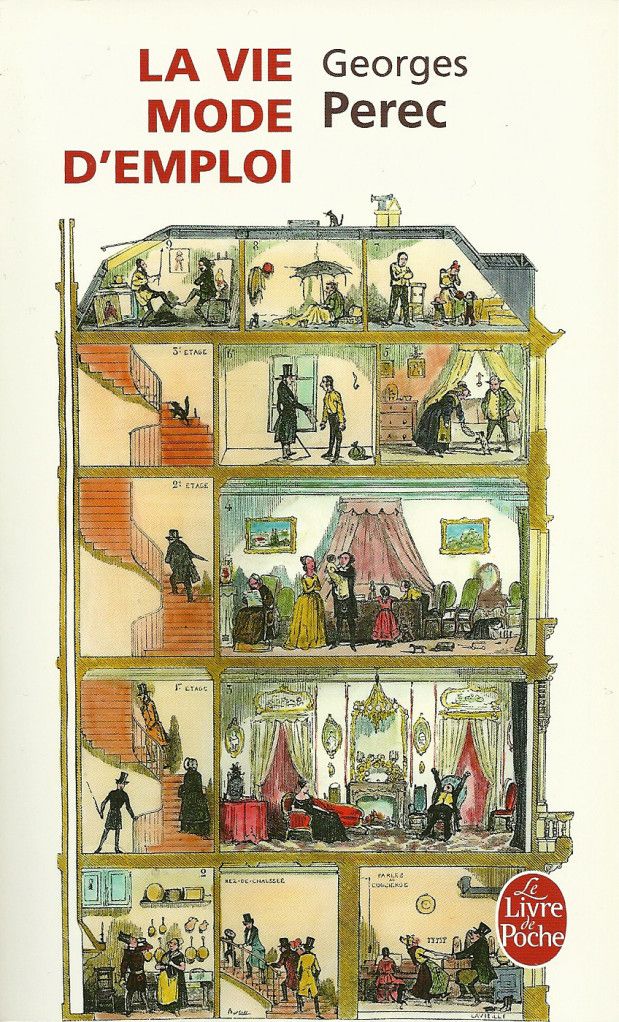

Another key thread is the painter Serge Valène's final project. Bartlebooth hires him as a tutor before embarking on his tour of the world, and buys himself a flat in the same block where Valène lives. He is one of several painters who have lived in the block over the century. He plans to paint the entire apartment block, seen in elevation with the facade removed, showing all the occupants and the details of their lives: Valène, a character in the novel, seeks to create a representation of the novel as a painting. Chapter 51, falling in the middle of the book, lists all of Valène's ideas, and in the process picks out the key stories seen so far and yet to come.

Both Bartlebooth and Valène fail in their projects: this is a recurring theme in many of the stories.

Life A User's Manual Pdf

Elements[edit]

Apartment block[edit]

One of Perec's long-standing projects was the description of a Parisian apartment block as it could be seen if the entire facade were removed, exposing every room. Perec was obsessed with lists: such a description would be exhaustive down to the last detail.

Some precedents of this theme can be found in the Spanish novel El diablo cojuelo [es] (1641, 'The Lame Devil' or 'The Crippled Devil') by Luis Vélez de Guevara (partially adapted to 18th century France by Alain-René Lesage in his 1707 novel Le Diable boiteux, 'The Lame Devil' or 'The Devil upon Two Sticks') and the 20th-century Russian novel The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov. Another well-known literary puzzle is Hopscotch (1963) by the Paris-resident Argentinian novelist Julio Cortázar.

While Bartlebooth's puzzle narrative is the central story of the book, 11 rue Simon-Crubellier is the subject of the novel. 11 rue Simon-Crubellier has been frozen at the instant in time when Bartlebooth dies. People are frozen in different apartments, on the stairs, and in the cellars. Some rooms are vacant.

The narrative moves like a knight in a chess game, one chapter for each room (thus, the more rooms an apartment has the more chapters are devoted to it). In each room we learn about the residents of the room, or the past residents of the room, or about someone they have come into contact with.

Many of the characters at 11 rue Simon-Crubellier, such as Smautf, Valène, Winckler, and Morellet, have a direct connection to Bartlebooth's quest. Thus, in those rooms the Bartlebooth puzzle-narrative tends to be carried further. Many of the narratives, however, are linked to Bartlebooth only by being related to the history of 11 rue Simon-Crubellier.

Knight's tour[edit]

A knight's tour as a means of generating a novel was a long-standing idea of the Oulipo group. Perec devises the elevation of the building as a 10×10 grid: 10 storeys, including basements and attics and 10 rooms across, including two for the stairwell. Each room is assigned to a chapter, and the order of the chapters is given by the knight's moves on the grid. However, as the novel contains only 99 chapters, bypassing a basement, Perec expands the theme of Bartlebooth's failure to the structure of the novel as well.

Life A User's Manual Perec

Lists[edit]

The content of Perec's novel was partly generated by 42 lists, each containing 10 elements (e.g. the 'Fabrics' list contains ten different fabrics). Perec used Graeco-Latin squares or 'bi-squares' to distribute these elements across the 99 chapters of the book. A bi-square is similar to a sudoku puzzle, though more complicated, as two lists of elements must be distributed across the grid. In the pictured example, these two lists are the first three letters of the Greek and Latin alphabets; each cell contains a Greek and a Latin character, and, as in a sudoku, each row and column of the grid also contains each character exactly once. Using the same principle, Perec created 21 bi-squares, each distributing two lists of 10 elements. This allowed Perec to distribute all 42 of his 10-element lists across the 99 chapters. Any given cell on the 10x10 map of the apartment block could be cross-referenced with the equivalent cell on each of the 21 bi-squares, for each chapter a unique list of 42 elements to mention could be produced.

The elements in Lists 39 and 40 ('Gap' and 'Wrong') are nothing more than the numbers 1 to 10; if Perec consulted the 'Wrong' bi-square and found, for example, a '6' in a given cell, he would ensure that the chapter corresponding to that cell would do something 'wrong' when including the particular fabric, colour, accessory or jewel the bi-squares for the lists in group 6 had assigned to the cell/chapter in question.

Perec also further sub-divided 40 of these lists into 10 groups of four (the sixth sub-group, for example, contains the lists 'Fabrics', 'Colours', 'Accessories' and 'Jewels',[1]) which gave the story-generating machine an additional layer of complexity.

Another variation comes from the presence of Lists 39 and 40 in the 10th sub-group; Lists 39 and 40 would sometimes number their own sub-group as the one to be tampered with in a given chapter. According to Perec's biographer, David Bellos, this self-reflexive aspect of Lists 39 and 40 'allowed him to apply 'gap' in such cases by not missing out any other constraint in the group ('gapping the gap') or by missing out a constraint in a group not determined by the bi-square number ('wronging the wrong') or by not getting anything wrong at all ('gapping the wrong')'.[1] The 41st and 42nd lists collectively form ten 'couples' (such as 'Pride & Prejudice' and 'Laurel & Hardy') which are exempt from the disruptions of the 'Gap' and 'Wrong' lists that affect the first forty lists.[2] It is important to note that Perec himself acknowledged the lists were often mere prompts; certain chapters include far fewer than 42 of their prescribed elements.

Appendix[edit]

An appendix section in the book contains a chronology of events starting at 1833, a 70-page index, a list of the 100 or so main stories, and a plan of the elevation of the block as the 10x10 grid. The index lists many of the people, places and works of art mentioned in the book:

- real, such as Mozart

- fictitious, such as Jules Verne's character Captain Nemo

- internally real, such as Bartlebooth himself

- internally fictitious: the characters in a story written by a schoolboy, for instance

Reception[edit]

In The New York Times Book Review, novelist Paul Auster wrote, 'Georges Perec died in 1982 at the age of 46, leaving behind a dozen books and a brilliant reputation. In the words of Italo Calvino, he was 'one of the most singular literary personalities in the world, a writer who resembled absolutely no one else.' It has taken a while for us to catch on, but now that his major work – Life: A User's Manual (1978) – has at last been translated into English it will be impossible for us to think of contemporary French writing in the same way again.'[3]

In a list of nontechnical books he has read, computer scientist Donald Knuth referred to this book as 'perhaps the greatest 20th century novel'.[4]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ abBellos, David (2010). Georges Perec: A Life in Words, pp. 600–602. Harvill Press, London. ISBN1846554209.

- ^Bellos, David (2010). Georges Perec: A Life in Words, p. 601. Harvill Press, London. ISBN1846554209.

- ^Paul Auster, 'The Bartlebooth Follies', The New York Times Book Review, November 15, 1987.

- ^Knuth, Donald. 'Knuth: Retirement'. Retrieved 8 October 2012.

External links[edit]

| Born | 7 March 1936 Paris, France |

|---|---|

| Died | 3 March 1982 (aged 45) Ivry-sur-Seine, France |

| Occupation | Novelist, filmmaker, essayist |

| Language | French |

| Spouse | Paulette Petras |

Georges Perec (born George Peretz) (French: [peʁɛk, pɛʁɛk];[1] 7 March 1936 – 3 March 1982) was a French novelist, filmmaker, documentalist, and essayist. He was a member of the Oulipo group. His father died as a soldier early in the Second World War and his mother was murdered in the Holocaust, and many of his works deal with absence, loss, and identity, often through word play.[2]

- 5Works

Early life[edit]

Born in a working-class district of Paris, Perec was the only son of Icek Judko and Cyrla (Schulewicz) Peretz, Polish Jews who had emigrated to France in the 1920s. He was a distant relative of the Yiddish writer Isaac Leib Peretz. Perec's father, who enlisted in the French Army during World War II, died in 1940 from untreated gunfire or shrapnel wounds, and his mother perished in the NaziHolocaust, probably in Auschwitz sometime after 1943. Perec was taken into the care of his paternal aunt and uncle in 1942, and in 1945 he was formally adopted by them.

Career[edit]

Perec started writing reviews and essays for La Nouvelle Revue française and Les Lettres nouvelles [fr], prominent literary publications, while studying history and sociology at the Sorbonne. In 1958/59 Perec served in the army as a paratrooper (XVIIIe Régiment de Chasseurs Parachutistes), and married Paulette Petras after being discharged. They spent one year (1960/1961) in Sfax, Tunisia, where Paulette worked as a teacher; these experiences are reflected in Things: A Story of the Sixties, which is about a young Parisian couple who also spend a year in Sfax.

In 1961 Perec began working at the Neurophysiological Research Laboratory in the unit's research library funded by the CNRS and attached to the Hôpital Saint-Antoine as an archivist, a low-paid position which he retained until 1978. A few reviewers have noted that the daily handling of records and varied data may have had an influence on his literary style. In any case, Perec's work on the reassessment of the academic journals under subscription was influenced by a talk about the handling of scientific information given by Eugene Garfield in Paris and he was introduced to Marshall McLuhan by Jean Duvignaud. Perec's other major influence was the Oulipo, which he joined in 1967, meeting Raymond Queneau, among others. Perec dedicated his masterpiece, La Vie mode d'emploi (Life a User's Manual) to Queneau, who died before it was published.

Perec began working on a series of radio plays with his translator Eugen Helmle and the musician Philippe Drogoz [de] in the late 60s; less than a decade later, he was making films. His first work, based on his novel Un Homme qui dort, was co-directed by Bernard Queysanne [fr], and won him the Prix Jean Vigo in 1974. Perec also created crossword puzzles for Le Point from 1976 on.

La Vie mode d'emploi (1978) brought Perec some financial and critical success—it won the Prix Médicis—and allowed him to turn to writing full-time. He was a writer in residence at the University of Queensland, Australia, in 1981, during which time he worked on 53 Jours (53 Days), which he would not finish. Shortly after his return from Australia, his health deteriorated. A heavy smoker, he was diagnosed with lung cancer. He died the following year in Ivry-sur-Seine, only forty-five years old; his ashes are held at the columbarium of the Père Lachaise Cemetery.

Work[edit]

Many of Perec's novels and essays abound with experimental word play, lists and attempts at classification, and they are usually tinged with melancholy.

Perec's first novel Les Choses: Une Histoire des Années Soixante (Things: A Story of the Sixties) (1965) was awarded the Prix Renaudot.

Perec's most famous novel La Vie mode d'emploi (Life a User's Manual) was published in 1978. Its title page describes it as 'novels', in the plural, the reasons for which become apparent on reading. La Vie mode d'emploi is a tapestry of interwoven stories and ideas as well as literary and historical allusions, based on the lives of the inhabitants of a fictitious Parisian apartment block. It was written according to a complex plan of writing constraints, and is primarily constructed from several elements, each adding a layer of complexity. The 99 chapters of his 600-page novel move like a knight's tour of a chessboard around the room plan of the building, describing the rooms and stairwell and telling the stories of the inhabitants. At the end, it is revealed that the whole book actually takes place in a single moment, with a final twist that is an example of 'cosmic irony'. It was translated into English by David Bellos in 1987.

Perec is noted for his constrained writing. His 300-page novel La disparition (1969) is a lipogram, written with natural sentence structure and correct grammar, but using only words that do not contain the letter 'e'. It has been translated into English by Gilbert Adair under the title A Void (1994). His novella Les revenentes (1972) is a complementary univocalic piece in which the letter 'e' is the only vowel used. This constraint affects even the title, which would conventionally be spelt Revenantes. An English translation by Ian Monk was published in 1996 as The Exeter Text: Jewels, Secrets, Sex in the collection Three. It has been remarked by Jacques Roubaud that these two novels draw words from two disjoint sets of the French language, and that a third novel would be possible, made from the words not used so far (those containing both 'e' and a vowel other than 'e').

W ou le souvenir d'enfance, (W, or the Memory of Childhood, 1975) is a semi-autobiographical work which is hard to classify. Two alternating narratives make up the volume: one, a fictional outline of a remote island country called 'W', at first appears to be a utopian society modeled on the Olympic ideal, but is gradually exposed as a horrifying, totalitarian prison much like a concentration camp. The second narrative is a description of Perec's own childhood during and after World War II. Both narratives converge towards the end, highlighting the common theme of the Holocaust.

'Cantatrix sopranica L. Scientific Papers' is a spoof scientific paper detailing experiments on the 'yelling reaction' provoked in sopranos by pelting them with rotten tomatoes. All the references in the paper are multi-lingual puns and jokes, e.g. '(Karybb & Szyla, 1973)'.[3]

David Bellos, who has translated several of Perec's works, wrote an extensive biography of Perec: Georges Perec: A Life in Words, which won the Académie Goncourt's bourse for biography in 1994.

The Association Georges Perec has extensive archives on the author in Paris.[4]

In 1992 Perec's initially rejected novel Gaspard pas mort (Gaspard not dead), which was believed to be lost, was found by David Bellos amongst papers in the house of Perec's friend Alain Guérin [fr]. The novel was reworked several times and retitled Le Condottière [fr][5] and published in 2012; its English translation by Bellos followed in 2014 as Portrait of a Man after the 1475 painting of that name by Antonello da Messina.[6] The initial title borrows the name Gaspard from the Paul Verlaine poem 'Gaspar Hauser Chante'[7] and characters named 'Gaspard' appear in both W, or the Memory of Childhood and Life a User's Manual, while in 'MICRO-TRADUCTIONS, 15 variations discrètes sur un poème connu' he creatively re-writes the Verlaine poem 15 times.

Honours[edit]

Asteroidno. 2817, discovered in 1982, was named after Perec. In 1994, a street in the 20th arrondissement of Paris was named after him, rue Georges-Perec [fr]. The French postal service issued a stamp in 2002 in his honour; it was designed by Marc Taraskoff and engraved by Pierre Albuisson. For his work, Perec won the Prix Renaudot in 1965, the Prix Jean Vigo in 1974, the Prix Médicis in 1978. He was featured as a Google Doodle on his 80th birthday.[8]

Works[edit]

Books[edit]

The most complete bibliography of Perec's works is Bernard Magné's Tentative d'inventaire pas trop approximatif des écrits de Georges Perec (Toulouse, Presses Universitaires du Mirail, 1993).

| Year | Original French | English translation |

|---|---|---|

| 1965 | Les Choses: Une histoire des années soixante (Paris: René Juillard, 1965) | Les choses: A Story of the Sixties, trans. by Helen Lane (New York: Grove Press, 1967); Things: A Story of the Sixties in Things: A Story of the Sixties & A Man Asleep trans. by David Bellos and Andrew Leak (London: Vintage, 1999) |

| 1966 | Quel petit vélo à guidon chromé au fond de la cour? (Paris: Denoël, 1966) | Which Moped with Chrome-plated Handlebars at the Back of the Yard?, trans. by Ian Monk in Three by Perec (Harvill Press, 1996) |

| 1967 | Un homme qui dort (Paris: Denoël, 1967) | A Man Asleep, trans. by Andrew Leak in Things: A Story of the Sixties & A Man Asleep (London: Vintage, 1999) |

| 1969 | La Disparition (Paris: Denoël, 1969) | A Void, trans. by Gilbert Adair (London: Harvill, 1994) |

| 1969 | Petit traité invitant à la découverte de l'art subtil du go, with Pierre Lusson and Jacques Roubaud (Paris: Christian Bourgois, 1969) | — |

| 1972 | Les Revenentes, (Paris: Editions Julliard, 1972) | The Exeter Text: Jewels, Secrets, Sex, trans. by Ian Monk in Three by Perec (Harvill Press, 1996) |

| 1972 | Die Maschine, (Stuttgart: Reclam, 1972) | The Machine, trans. by Ulrich Schönherr in 'The Review of Contemporary Fiction: Georges Perec Issue: Spring 2009 Vol. XXIX, No. 1' (Chicago: Dalkey Archive, 2009) |

| 1973 | La Boutique obscure: 124 rêves, (Paris: Denoël, 1973) | La Boutique Obscure: 124 Dreams, trans. by Daniel Levin Becker (Melville House, 2013) |

| 1974 | Espèces d'espaces [fr] (Paris: Galilée 1974) | Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, ed. and trans. by John Sturrock (London: Penguin, 1997; rev. ed. 1999) |

| 1974 | Ulcérations, (Bibliothèque oulipienne, 1974) | — |

| 1975 | W ou le souvenir d'enfance (Paris: Denoël, 1975) | W, or the Memory of Childhood, trans. by David Bellos (London: Harvill, 1988) |

| 1975 | Tentative d'épuisement d'un lieu parisien (Paris: Christian Bourgois, 1975) | An Attempt at Exhausting a Place in Paris, trans. by Marc Lowenthal (Cambridge, MA: Wakefield Press, 2010) |

| 1976 | Alphabets illust. by Dado (Paris: Galilée, 1976) | — |

| 1978 | Je me souviens, (Paris: Hachette, 1978) | Memories, trans./adapted by Gilbert Adair (in Myths and Memories London: Harper Collins, 1986); I Remember, trans. by Philip Terry and David Bellos (Boston: David R. Godine, 2014) |

| 1978 | La Vie mode d'emploi (Paris: Hachette, 1978) | Life a User's Manual, trans. by David Bellos (London: Vintage, 2003) |

| 1979 | Les mots croisés, (Mazarine, 1979) | — |

| 1979 | Un cabinet d'amateur, (Balland, 1979) | A Gallery Portrait, trans. by Ian Monk in Three by Perec (Harvill Press, 1996) |

| 1979 | film-script: Alfred et Marie, 1979 | — |

| 1980 | La Clôture et autres poèmes, (Paris: Hachette, 1980) – Contains a palindrome of 1,247 words (5,566 letters).[9] | — |

| 1980 | Récits d'Ellis Island: Histoires d'errance et d'espoir, (INA/Éditions du Sorbier, 1980) | Ellis Island and the People of America (with Robert Bober), trans. by Harry Mathews (New York: New Press, 1995) |

| 1981 | Théâtre I, (Paris: Hachette, 1981) | — |

| 1982 | Epithalames, (Bibliothèque oulipienne, 1982) | — |

| 1982 | prod: Catherine Binet's Les Jeux de la Comtesse Dolingen de Gratz, 1980–82 | — |

| 1985 | Penser Classer (Paris: Hachette, 1985) | 'Thoughts of Sorts', trans. by David Bellos (Boston: David R. Godine, 2009) |

| 1986 | Les mots croisés II, (P.O.L.-Mazarine, 1986) | — |

| 1989 | 53 Jours, unfinished novel ed. by Harry Mathews and Jacques Roubaud (Paris: P.O.L., 1989) | 53 Days, trans. by David Bellos (London: Harvill, 1992) |

| 1989 | L'infra-ordinaire (Paris: Seuil, 1989) | — |

| 1989 | Voeux, (Paris: Seuil, 1989) | — |

| 1990 | Je suis né, (Paris: Seuil, 1990) | — |

| 1991 | Cantatrix sopranica L. et autres écrits scientifiques, (Paris: Seuil, 1991) | 'Cantatrix sopranica L. Scientific Papers' with Harry Mathews (London: Atlas Press, 2008) |

| 1992 | L.G.: Une aventure des années soixante, (Paris: Seuil, 1992) Containing pieces written from 1959–1963 for the journal La Ligne générale: Le Nouveau Roman et le refus du réel; Pour une littérature réaliste; Engagement ou crise du langage; Robert Antelme ou la vérité de la littérature; L'univers de la science-fiction; La perpétuelle reconquête; Wozzeck ou la méthode de l'apocalypse. | — |

| 1993 | Le Voyage d'hiver, 1993 (Paris: Seuil, 1993) | The Winter Journey, trans. by John Sturrock (London: Syrens, 1995) |

| 1994 | Beaux présents belles absentes, (Paris: Seuil, 1994) | — |

| 1999 | Jeux intéressants (Zulma, 1999) | — |

| 1999 | Nouveaux jeux intéressants (Zulma, 1999) | — |

| 2003 | Entretiens et conférences (in 2 volumes, Joseph K., 2003) | — |

| 2012 | Le Condottière (Éditions du Seuil, 2012) | Portrait of a Man Known as Il Condottiere, translated by David Bellos (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014) |

| 2016 | L'Attentat de Sarajevo (Éditions du Seuil, 2016) | — |

Films[edit]

- Un homme qui dort, 1974 (with Bernard Queysanne, English title: The Man Who Sleeps)

- Les Lieux d'une fugue, 1975

- Série noire (Alain Corneau, 1979)

- Ellis Island (TV film with Robert Bober)

References[edit]

- ^Jenny Davidson, Reading Style: A Life in Sentences, Columbia University Press, 2014, p. 107: 'I have an almost Breton name which everyone spells as Pérec or Perrec—my name isn't written exactly as it is pronounced.'

- ^David Bellos (1993). Georges Perec. A life in words. London: Harvill/HarperCollins. ISBN0879239808.

- ^'Mise en évidence expérimentale d'une organisation tomatotopique chez la soprano (Cantatrix sopranica L.)'(in French)

'Experimental demonstration of the tomatotopic organization in the Soprano (Cantatrix sopranica L.)' - ^'Association Georges Perec'.

- ^'The Letter Vanishes' by James Gibbons, Bookforum, December/January 2006

- ^'Georges Perec's Lost Novel' by David Bellos, The New York Review of Books, 8 April 2015

- ^David Bellos (1993). Georges Perec: A Life in Words : a Biography. D.R. Godine. p. 108. ISBN978-0-87923-980-0.

- ^'Georges Perec's 80th Birthday'. www.google.com. Retrieved 7 March 2016.

- ^Georges Perec: 'Le grand palindrome' in La clôture et autre poèmes, Hachette/Collection P.O.L., 1980

Further reading[edit]

Biographies

- Georges Perec: A Life in Words by David Bellos (1993)

Criticism

- The Poetics of Experiment: A Study of the Work of Georges Perec by Warren Motte (1984)

- Perec ou les textes croisés by J. Pedersen (1985). In French.

- Pour un Perec lettré, chiffré by J.-M. Raynaud (1987). In French.

- Georges Perec by Claude Burgelin (1988). In French.

- Georges Perec: Traces of His Passage by Paul Schwartz (1988)

- Perecollages 1981–1988 by Bernard Magné (1989). In French.

- La Mémoire et l'oblique by Philippe Lejeune (1991). In French.

- Georges Perec: Ecrire Pour Ne Pas Dire by Stella Béhar (1995). In French.

- Poétique de Georges Perec: «...une trace, une marque ou quelques signes» by Jacques-Denis Bertharion (1998) In French.

- Georges Perec Et I'Histoire, ed. by Carsten Sestoft & Steen Bille Jorgensen (2000). In French.

- La Grande Catena. Studi su 'La Vie mode d'emploi' by Rinaldo Rinaldi (2004). In Italian.

External links[edit]

- Petri Liukkonen. 'Georges Perec'. Books and Writers

- Université McGill: le roman selon les romanciers (French) Inventory and analysis of Georges Perec non-novelistic writings about the novel

- Perec's 'Negative Autobiography' at the Wayback Machine (archived 23 December 2007)

- Récits d'Ellis Island' on IMDb

- Un homme qui dort on IMDb

- Les Lieux d'une fuge on IMDb

- Georges Perec on IMDb